A Business Case for Make-Believe

Our most cost-effective method to understand customers’ needs might be to pretend.

When a server asks, “How was dinner?” Many of us respond to a meal not worthy of recommendation with, “It was good, thank you.” And really, why would a restaurant expect any other answer? A customer pays money for a meal, not to participate in market research. It takes less effort to never return to the restaurant than to converse about its needed improvements. There is always another restaurant.

The Problem with Asking

How do we know what our ideal customer wants?1 We can create surveys! We can ask, “What is one thing we could do to improve?” or “What would you suggest to help us improve our service?” Then, like a wish on a star, we can hope that we’re hearing from a truly representative sample of our customers—rather than just the most vocal ones—and have faith that we get an accurate recall of their experience, an authentic response with proactive actions—instead of suggestion to “Do better next time.” Hmmph.

Why not a focus group? We can get focused, in-depth qualitative insights that build off the multiple responses, revealing underlying motivations and attitudes…

But first, a question, you should answer out loud.

"How are you doing? Personally? Good, just fine?"

In the context of this situation, reading online by ourselves is not appropriate—or possible, really—for us to hear and get the details of your feelings. This is the flaw with focus groups and, in general, asking people's opinions. It's filtered.

People's behavior changes when they know they’re being observed—a phenomenon known as the Hawthorne Effect. The term comes from 1920s experiments at Western Electric's Hawthorne Works, where researchers found worker productivity increased simply because people knew they were being watched and studied—regardless of the actual changes being tested.

Despite that, we can get a lot of useful information from focus groups if we have the resources to organize and run them. I.e., you need money and time, a few bucks for participant incentives, facility rental, moderator fees, and analysis costs.

What If We Stop Asking?

What happens if we stop asking customers and maybe ask ourselves? What if, instead of hoping surveys will tell us the truth or focus groups will reveal a magic answer, we just... pretend? Pretend like some of the most successful business leaders in history did.

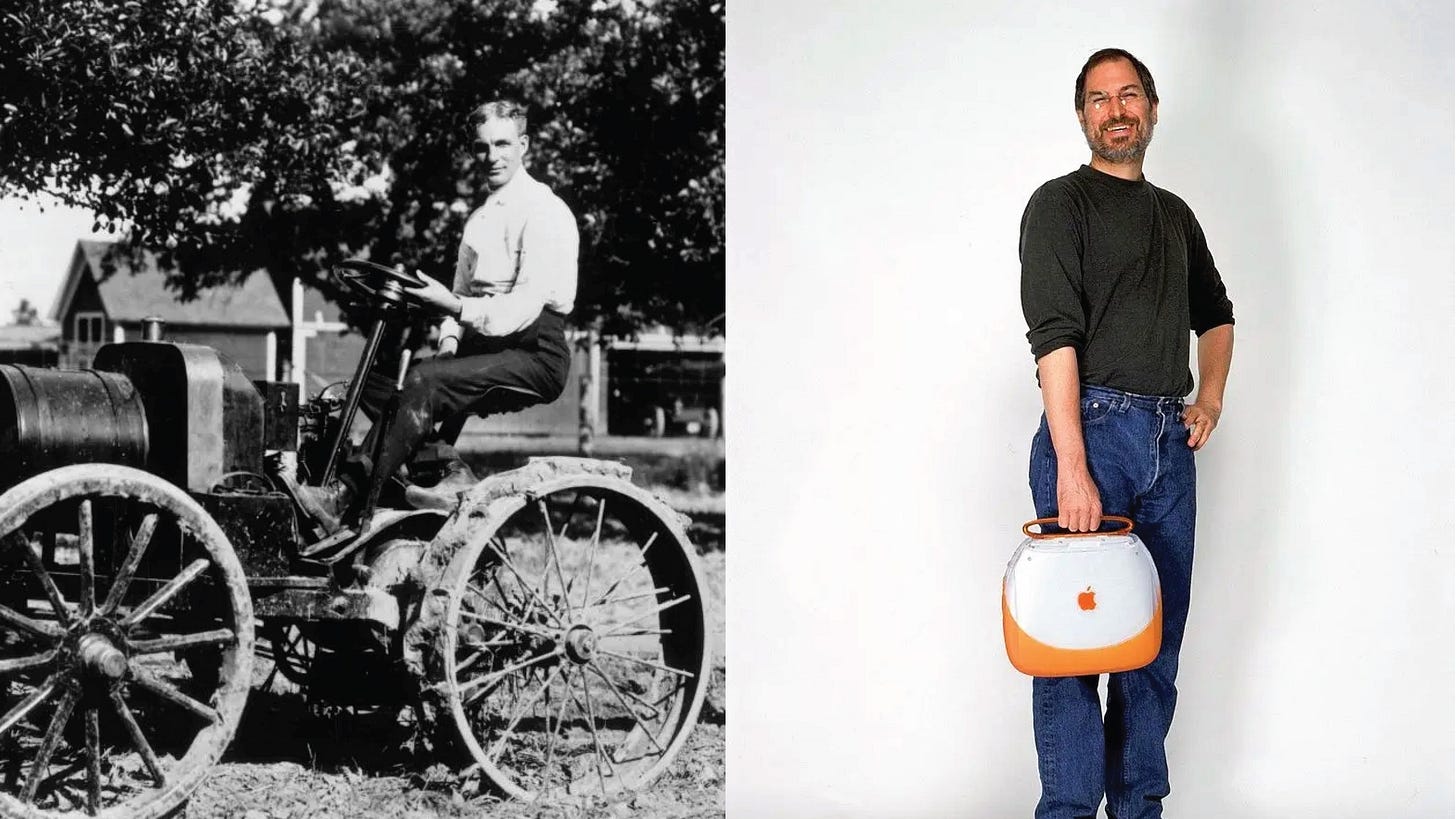

It's never been verified that Steve Jobs said, "If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses." And there's no proof that Henry Ford did either. However, through Steve and Henry's actions and behaviors, both of them seemed to believe it to be true. Each of them suggested that they knew more than the customer. Neither one of them asked for surveys or focus groups, and they didn't pull massive data sets to make decisions. Instead, like a 6-year-old, they pretended. What's not often talked about is the length to which they would pretend.

In his factory cars, Henry used to drive long distances across America. He even used to informally test his cars on long camping trips with Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and John Burroughs. They called themselves the "Vagabonds" and would spend weeks exploring the American countryside, sleeping in tents under the stars. Henry would meticulously observe how his vehicles handled different terrains, weather conditions, and the punishing demands of long-distance travel. He'd often stop to tinker with the engines, making mental notes about improvements needed for future models. These weren't just pleasure trips—they were rolling laboratories where Henry could experience firsthand what his customers would face on America's rough, early roads.

Steve used to spend much of his days using products, telling engineers how much he liked or hated using them. Before they released the iMac and iBook, he was seen pacing hallways, carrying them around from meeting to meeting. He would obsess over the smallest details – the curve of the handle on the iBook, the transparency of the iMac's case, even the sound the device made when it was turned on. He'd use prototypes at home, bringing them back with lists of changes: this button feels wrong, that startup time is too slow, this screen isn't bright enough. Steve would often call engineers in the middle of the night after discovering something that bothered him during his personal testing. He treated each product as if he were its first and most demanding user, believing that if it delighted him, it would delight others.

What's Stopping Us?

All of us, in some form, have imagined what our customers are going through. What stops us from doing what Henry and Steve did? We use mental shortcuts to jump to conclusions. We get overconfident because we “know this business better than anyone.” We stereotype our customers and make judgments of them because “we’ve seen it all before.” The most successful leaders and brands built in this country used empathetic, multi-perspective thinking. So how do we practice what these great American industrialists have? We pretend.

But what about all our data? Our analytics? Our quarterly reports? Here's the thing—pretending isn't about throwing information away. It's finding the problems worth measuring.

How do we pretend?

If we own a restaurant, we make reservations on the busiest night; we sit in the dining room, we feel our chair, we read the menu, taste the food, and pay as our customers do. These are the things worth measuring and fixing. Our data can tell us that customers aren't staying as long as they used to. But pretending tells us why.

In terms of cost and execution over results, there is no higher value in marketing or research than pretending. It will help us build better products and better services. You want to play pretend?

Our resources are limited. Don’t water weeds