Context Shapes Expectations

2. How Unspoken Signals Can Define Our Business Growth

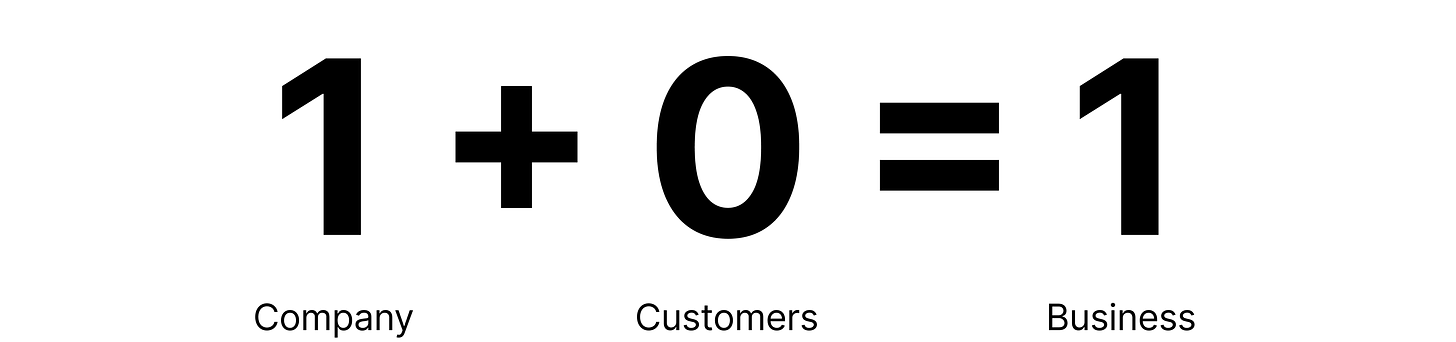

As business owners, we have a tendency to think of business like this: We’ve got an idea that fulfills a need. People tell us they like the idea, and we have investors who believe it will work. We’re in business!

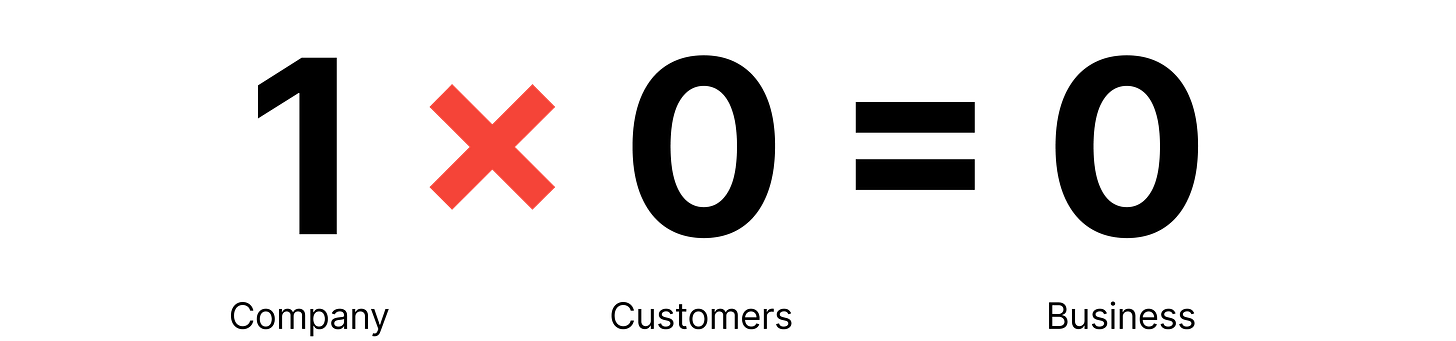

This can be deceptive math that takes our euphoric, indomitable spirit on a slide of self-doubt and distress. Rather than an addition problem, business should be regarded as a multiplication problem.

Though our business concept may fulfill a need, and people say they’d buy it or invest in it, if our company doesn’t produce a customer, it is not a business. We’re not “in” business.

The only valid objective of business is to create customers.1 The most excellent service, solution, or product will never outweigh the value of someone willing to pay. The others will not exist without the one—the lack of hydration wilts.

Fulfilling a need or a want is a partial win. To have customers believe us, based on the expectations we imply—this is where the match lights, when the money is laid down—it’s the moment we become a business. And it’s the critical reason to look up, pay attention, and focus on the expectations we build for ideal customers.

Lessons from Home

For a business to prosper, we must manage the expectations of our ideal customer—just as we manage expectations with those we live with. In both cases, what's left unsaid can be as significant as what's explicitly stated.

Let's look at a common scenario. Our spouse heads out and says, "I'm going out to visit Heather. Will you put away the dishes?”

We say, "Okay."

What do they expect us to do?

Of course, they want us to put away the dishes, but for some keen observers—and those with a good sense of emotional intelligence—we believe the request was greater. What they really wanted was for us to put the dishes away before they came back.

But look at the request again; that’s not what they said. There is no mention of a time. What if we don’t put the dishes away by the time they come back? Well, they’re upset, but not because they weren’t put away. They’re upset because they expected them to be put away by the time they got back. This is upsetting to them. Is this irritation unfair? Who cares, it doesn’t matter; the expectation was set whether we like it or not.

What could a pair of 9-month-old twins do for this situation? Try this scenario again; this time, we’re caring for two wild-eyed, helpless, yet self-determined little ones. Our spouse leaves saying the same thing as before. When they come back, and the dishes aren’t put away, are they upset? Probably not to the same extent. What's implied is very different; the expectation of 9-month-old twins is to expect the unexpected.

This is what good branding does: it creates a context that shapes expectations. Just as parents of twins are given more grace due to their understood circumstances, a well-branded business establishes a clear context for how it operates and what our ideal customer should expect.

Air Mattresses and Small Markets

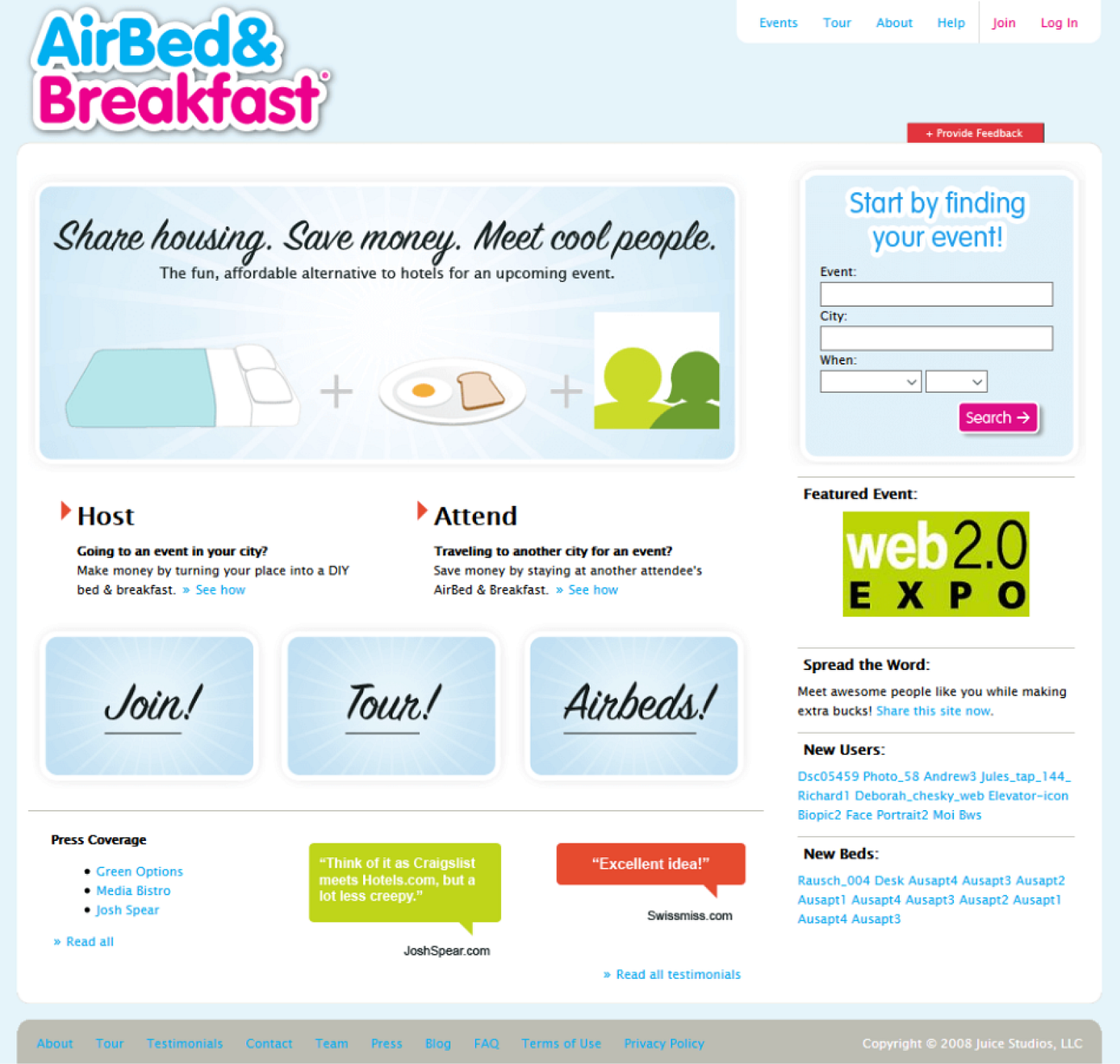

Branding alone doesn’t make an 80-billion-dollar company like Airbnb. But, if we’re not careful, we could spend inadvertent efforts to force a square peg idea into a round hole.

What if Airbnb continued to imply their ideal customer was someone who enjoyed a fitful sleep on an air mattress in a stranger’s home, awakening to eggs and bacon cooked and served to you by an amateur in an unregulated kitchen? It’s a small market and one that led Airbnb to the brink of dissolving its business.

To be absolutely clear, this is the original Airbnb brand. The market of this implication was so small that they were doing better as a breakfast cereal company—no joke.2

In branding, what we imply creates an expectation. We must be very careful with the message we send. For the long-term viability of our business, this expectation needs to fit the wants of our ideal customer.

Whether we like it or not, what we imply sets an expectation.

Whether we like it or not, that expectation must fit the wants of our ideal customer—if we want our business to survive.